DENK MAL AM ORT

7. / 8. Mai 2016

On 7/8 May 2016, the 71st anniversary of the end of World War Two, DENK MAL AM ORT paid homage at

authentic sites to the Jewish citizens of Berlin who were persecuted, expelled and murdered.

With creative ideas, initiatives, individuals and house communities remembered a particular person where they had actually lived in Berlin.

Events took place at sixteen different sites in the city ranging from reading names to biographies, from talks with

contemporary witnesses to readings, from film screenings, art exhibitions, installations, music and audio to drawings, poetry and documentation.

The beginning was marked by Denise Citroen, a Dutch woman who came to Berlin from Amsterdam to speak about how

OPEN JEWISH HOMES had evolved in the Netherlands. DENK MAL AM ORT is based on this idea but extended to include

all those who were ostracized, persecuted, robbed or murdered during the Nazi era.

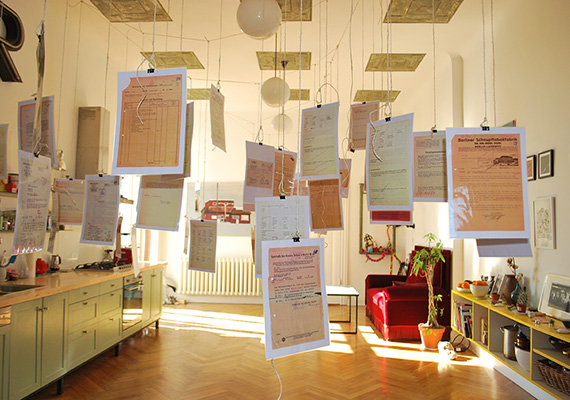

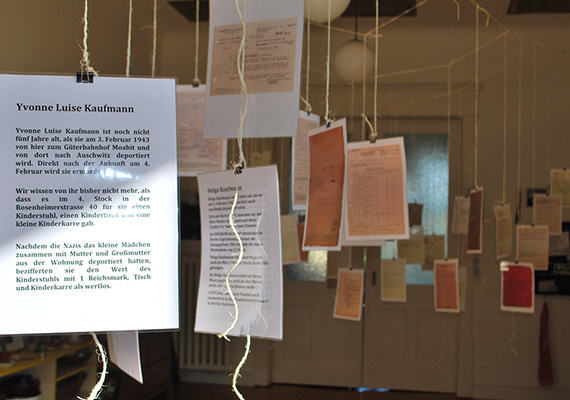

My temporary installation composed of documents testifying to persecution and robbery commemorates nine

people who lived in a fourth floor apartment in Rosenheimer Strasse 40 in the Schöneberg district of Berlin

and were deported: three families with two small children and a single woman pensioner.

LOCKED OUT OF EUROPE

Video Installation (14:54 min, 2014)

Pope Francis calls it the globalization of indifference. We are the travellers of permanent transit, say the refugees.

The European Union is a house with 28 open doors. We Europeans are pleased at this newly acquired freedom and peace and the possibility of living and working in whatever area of Europe we choose.

The doors of Europe are locked tight on the outside, especially southwards. Europe’s furthest southern border is not on European soil but in Africa. Melilla, a Spanish exclave in Morocco with approx. 80 000 inhabitants, is so far away from Europe and our peaceful existence that we fail to see what is happening at this, our external border.

Melilla was fenced in with funds from the European Community. The border system is eleven kilometres long and consists of three consecutive fences, one of which is six metres high. Floodlights, movement detectors, thermal cameras, watchtowers and patrol vehicles are reminiscent of the inner-German border. Very few attempts to scale the fence succeed. Migrants and refugees from Sub-Saharan Africa, Syria and Afghanistan are injured by NATO razor wire or by border guards. Lacerated, they drop to the ground and, without receiving medical assistance, are frequently deported back to Morocco on the spot.

Jani Pietsch explored the fence on foot and by bicycle. Her collage of video and sound recordings translocates Europe’s most southern border to the centre of Europe.

SHIFTING IDENTITIES

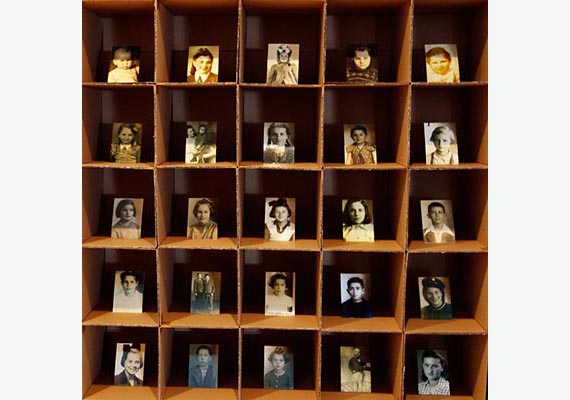

Jewish Survivor Children, Installation (2013)

From 2011-2013, I took part in a Polish-German art project

(www.silesiatopia.de) in the region of Zabrze, Poland. Ten visual artists from

Poland and Berlin were asked to translate their personal view of the Upper

Silesian region into an art form.

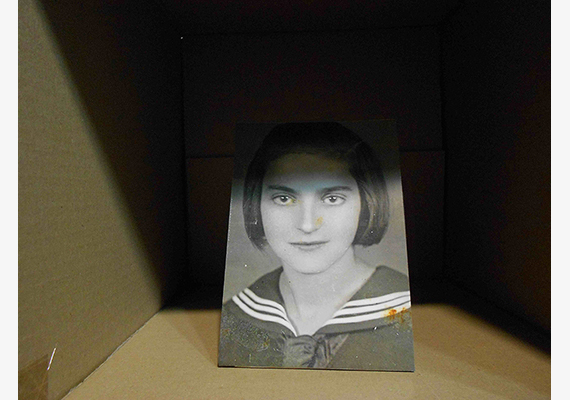

My research in Zabrze focused on the absence

of people. Empty spaces, invisible voids as expressions of loss, of a vanished

Polish Jewish world. While doing online research in the Ghetto Fighters’ House

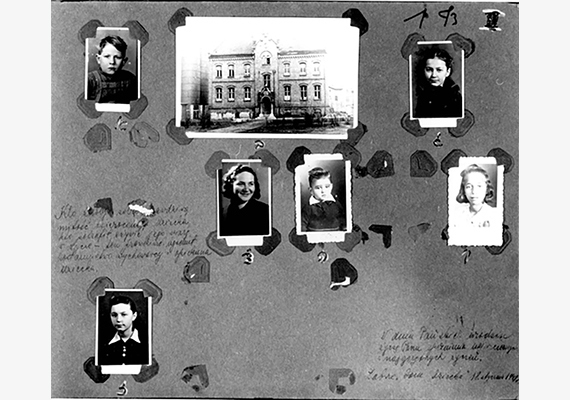

archives in Israel, I came across the The Album of the Jewish Children’s Home in

Zabrze. Compiled in 1950 as a gift to “the father of the Jewish orphans in

Poland”Yeshayahu Drucker1, the album contains about 196 small black-and-white

portrait photographs of survivor children on twenty-two black pages.

Most of the 196 Polish Jewish children in the “album” survived the Holocaust in Poland because non-Jewish Poles rescued them. Some of the children found shelter in Polish families. Some were forced to roam through forests and villages, hunting for food and struggle each day anew for survival. Others hired themselves out as labour in various villages or found shelter in church-sponsored orphanages or convents. Many were forced to live under false identity. Some were so young when separated from their parents that they forgot their real names and identity.

Drucker traveled throughout Poland, locating and redeeming Jewish children. Many of the children had no family relations in Poland or even abroad, yet they were the sole survivors of entire Jewish families. Some of these children were even baptised after the war. Drucker began to negotiate with the Poles, and to pay the families for their financial outlay during the war. He arrived in an army car, he was dressed in his officer’s uniform that gave the impression that the government wanted the matter settled and the children released. He personally led many of the hidden children to the Jewish Children’s Home in Zabrze. 1945 this Home was established in the former small synagogue of Zabrze and funded by the Central Committee of the Jews in Poland, the American Joint Distribution Committee, and contributions organized by rabbis overseas.

All of the young children and teenagers in the Children’s Home in Zabrze were Holocaust survivors. All of them had been rescued. They were alive and safe, and childcare workers, who were themselves survivors, looked after them lovingly. But each single child felt afraid, alone, isolated, apart, and had to cope with the devastating fact that she or he was the sole survivor of their family. Some were traumatized a second time when they were taken away from their foster families and stripped of their new Polish Catholic identity. Every single child who spent some time in the Children’s Home in Zabrze went through a difficult and strenuous period of waiting, of transition but also of departure to a new life. When the cold war had come to Poland all Jewish Children’s Homes2 were closed down by the Polish government that was now suspicious of all Zionist, Yiddish and Hebrew activities.

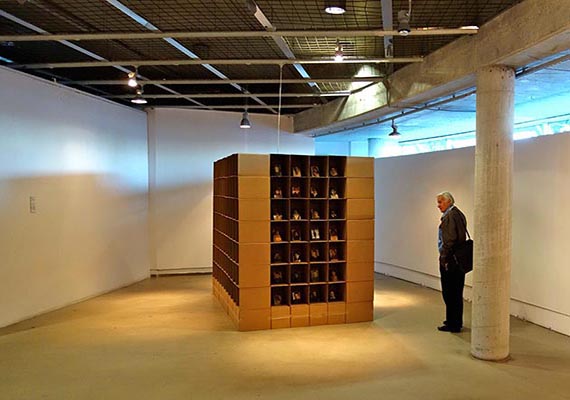

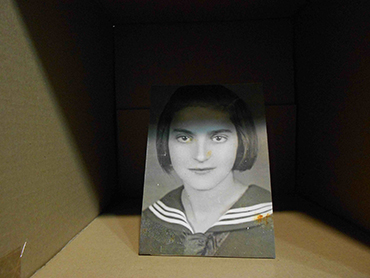

The Album of Yeshayahu Drucker became the basis of my installation SHIFTING IDENTITIES. The installation consists of 196 brown cardboard boxes (25 x 25 x 40 cm) open on one side, each of which displays a portrait photograph of one of the children (10 x 14 cm). The dark space behind the photographs suggests the discontinuity and vulnerability of the children, and their loneliness. Cardboard expresses the temporary nature of the situation in the Jewish Children’s Home in Zabrze. Using cardboard as the main material for the installation refers to SAFE – HOUSING – FOOD – CARE – WARMTH – RESCUED. On the other hand, the more general meaning of cardboard is FRAGILE – MAKESHIFT – IN BETWEEN – IN TRANSITION – MOVE. For more than a hundred years a cardboard box has been well known as the poor relative of the suitcase. Today homeless people all over the world use cardboard as a form of shelter. 196 cardboard boxes are stacked to form a house (2.85 x 2.05 x 1.80 m). The cardboard house can be entered through a small gap (0.50 m). On a monitor inside the SHIFTING IDENTITIES installation, three of the rescued children, whom I had the opportunity to meet in Israel, speak about their survival in Poland and their stay in the Jewish Children’s Home in Zabrze. Next to David Danieli (Dawid Danielski), who was hidden by a neighbour in Rybnik for four years, it is Orna Keret (Fela Kożuch) and Ruth Marks (Roma Głowińska). Orna Keret survived the annihilation of Warsaw Ghetto on her own. As a child Ruth Marks was deported from her hometown Kalisz to Ghetto Sandomierz. She fled the Ghetto and was finally hidden by a catholic woman in a village near Warsaw.

1 William Leibner: Yeshayahu Drucker. Father of the Jewish Orphans in Postwar Poland, 17/1/2010, Yad Vashem Archives, Record Group 033, Testimonies, Diaries and Memoirs Collection no. 8309.2 Homes for Jewish survivor children were established in Helenowek/Lublin, in Lodz, in Otwock/Warsaw, in Krakow, in Chorzów, in Zakopane, in Zabrze and in Geszcze Pusze. At the end of 1945 there were already 11 Jewish foster homes in Poland. All of these homes had one basic goal: get the children to Eretz Israel. This goal became even more prominent after the Kielce pogrom on Juli 4th 1946 in which 46 Jewish survivors were killed and over 40 injured.

IN THE ALPS

Installation (2009, together with artist Isabel Mertel, New Zealand)

Four nations fought in the First World War among the high mountains of the

Alps, and to this day the debris of war remains scattered there. But the beauty

of the unique palaeozooic coral reef of the Carnic Alps is timeless. It was

formed 300 million years ago along the coast of the ocean separating the

European and African continents.

A flat barque, formed by piling up layers of

rock on the 2500-metre-high ridge in the September hail, suggests the early

oceans, suggests continents and planets without borders.